Blaise Pascal, Emily Dickinson, and Ludwig Wittgenstein all performed acts of curation on their works. Whether with thread, bundles, or experiments in assembly, the three writers had unusual ways they wanted their works to be collected. Consequently, it has been difficult, for me, to read these texts without engaging with the methods of their collections, or thinking of others who had similar acts of collection. I do not wish to use this blog post to theorise on why Pascal, Dickinson, and Wittgenstein worked in such a way, but rather, to explore how their methods effect the knowing reader, and how the reader then experiences their work.

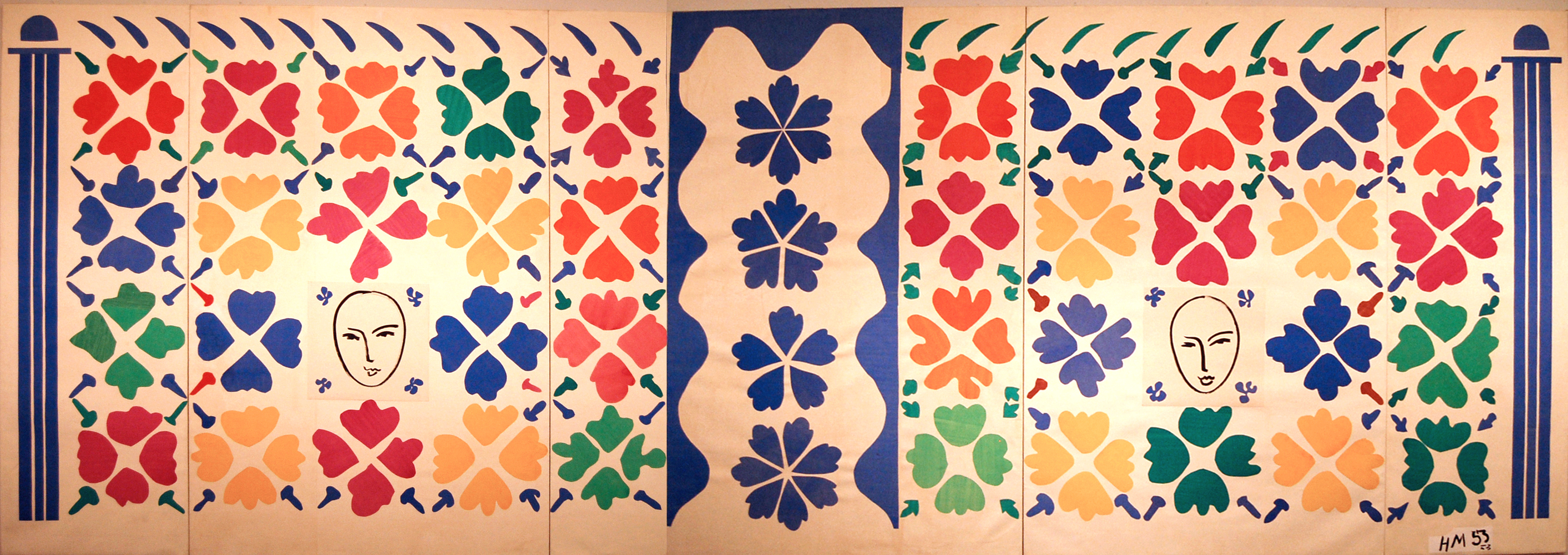

However, before turning to the three writers who make up the course I would like to take a moment to discuss another artist who works and thinks in pieces: Henri Matisse. During his later years, Matisse, suffering from ill health, lost the ability to paint in the way he once had. Matisse needed a new method of creating his art and began working with “cut-outs”. The method was simple, he has lost his ability to paint precisely so cut pieces out of pre-painted pages and, then, bundled them together to create collage style paintings. The 2014 exhibition, at the Tate Modern in London, showed the different stages and versions of composition. It is reminiscent of Wittgenstein’s experiments in the assembly of his pieces. The “cut-outs”, as the art world has named them, are also in a similar style to Matisse’s earlier work even though their crafting and presentation are different. The reclining and dancing figures are gone but what they were against remains. Matisse has used the cut-outs to bring the background into the foreground.

During the week’s reading I have been thinking about why I was thinking of Matisse. It is, I believe, how knowing the collection method effects the understanding of the work. The different ways the same pieces are collected creates different emphases. Reading Emily Dickinson offers similar possibilities. Her poems are collected in two ways: chronologically and by fascicle. There is some overlap, of course, but reading them in these two orders offers a different overall experience. Dickinson uses pronouns ambiguously, without real clarity as to who, or what, they stand in for. I found myself following different figures through her poems depending on whether I was reading them in chronological order or in the order dictated by fascicle.

The poem numbered 131, for example, has two figures the speaker and an unspecified she. Reading this poem chronologically, one may carry over the female “mama” figure, or perhaps the sparrow in the previous poem, 130. However, 131 appears in Fascicle 10 following a series of poems featuring only inanimate objects (244-47). There is then, an added mystery to the she in 131; even more so when the figures increase and a direct address of “you” is made. Dickinson plays with the relationship of the speaker of her poems with the other, often ambiguous figures in it, and the reader. They oscillate between inviting a reader in to an private world and excluding one from it. The poems, at times, feel intrusive to read however, it is when Dickinson is experimenting with punctuate that this dual movement exists most. The dashes in poem 80 make it unclear whether it is the “you” or the “I” of the poem which is “unsuspecting” or whether the feeling is “almost- a loneliness” or whether the feeling is “almost” in existence. The frequency with which Dickinson has an unexpected turn, or word at the end of her poem causes a similar effect: in her own words “perplexity”(99).

Pascal in his Pensées has a similarly convoluted relationship between writer and reader. His, however, is more informed by the history of the crafting and production of his work than Dickinson’s. Not all of the pieces in Pensées were collected, and what Pascal intended the work to be in unclear. It has elements of both a rhetorical piece and elements that are more immediate and appear personal to Pascal. It is these more internally inflected pieces that show similarities to Dickinson and Matisse. To take “Vanity” as one example, Pascal makes statements without offering much in the way of explanation. “An inch or two of cowl can put 25,000 monks up in arms” (18) has no direct relevance to the statements on either side of it nor is it clear whether Pascal means it to be a criticism or whether it is purely an observation. Similarly with “we do not choose as captain of a ship the most highly born of those aboard” (30). The logic of the statement is easy to follow— that is not a reasonable way to choose a captain— but Pascal offers no other possibility. Readers are left to puzzle what they would do, and what Pascal means by it.

With Wittgenstein, too, the knowledge of the way he crafted his work effects how it is read. In his preface he claims “until recently I had really given up the idea of publishing my work in my lifetime.” What then did Wittgenstein make of his work? And how much did it change once he knew it was to be published in his lifetime? The answers to these questions I have not (yet[?]) found in his work but it leads me to another which I am sure will follow me through his Philosophical Investigations, Pascal’s Pensées, and Dickinson’s oeuvre. How much should this knowledge of collection, curation, experimentation in assembly, or intention effect the way these texts are read? Is it the same for each of the three writers? Or for Wittgenstein, with his more complete work, does it matter more?

As I mentioned in class, I was really intrigued by the comparison to Matisse’s cut-outs. I want to think more about what your observation that Matisse uses them to “bring the background into the foreground.” Leads me then to ask whether or not everything is foreground in each of our writers. If true of, e.g. Dickinson, it would be true in a different way that for either Pascal or Wittgenstein.

More generally – the degree to which assembly (and the possibility of re-arrangement) enters into the method of all three writers, which you discuss. On the other hand, each remark or poem has a lot of internal structure – something we would not say of Matisse’s cut outs, though I guess details in the variability of their contours might reward attention (maybe not).

Knowing the pieces are, as you say, curated indeed influences how one thinks about them and one a guiding consideration for me in thinking to put these three writers together in the first place. At the same time a certain “brokenness” or use of discontinuity is internal to the way each of them writes (perhaps least so of Pascal? – but that’s in part because the arrangement of the Pensées seems in view of another order, no?

I’m especially interested by the connection you make between the collection of pieces as method and the undertain relationship between writer and reader. This comes across in Dickinson’s use of pronouns, but it’s there in the “dialogical” quality of the Investigations too.